In an era where globalisation is nearing its death, how are international organisations still relevant in the management of economics and trade?

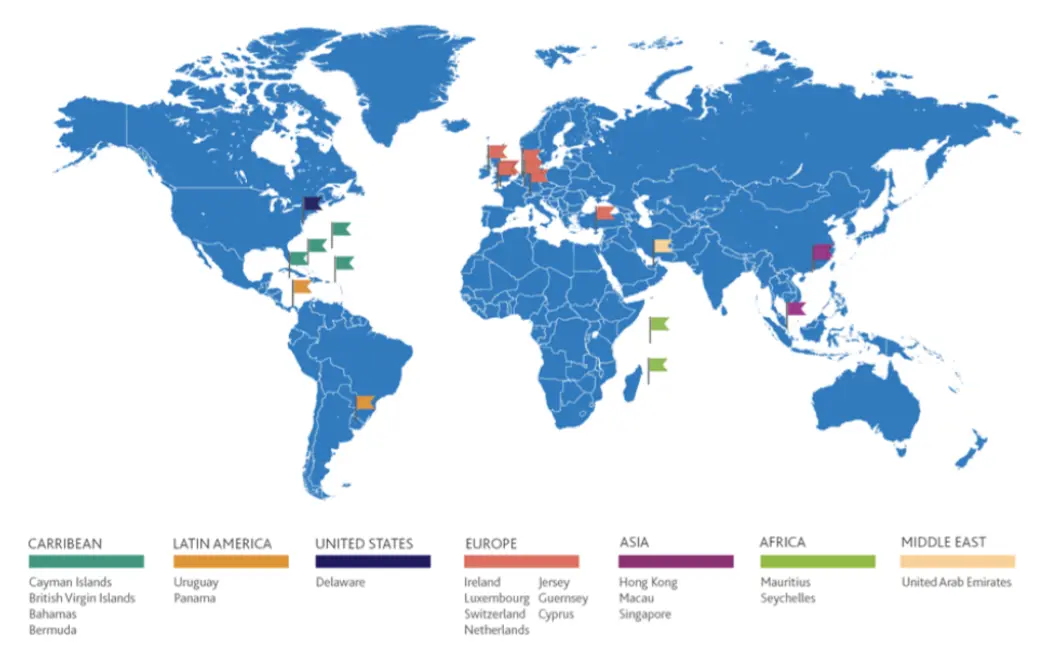

For developing nations, becoming an Offshore Financial Centre (OFC) creates a pathway that attracts global investors and leads to a flourishing economy. OFCs are defined by the IMF as a “country or jurisdiction that provides financial services to nonresidents on a scale that is disproportionate with the size and financing of its domestic economy.” By providing tax arbitrage opportunities in a confidential and secure method, OFCs generate income that results in higher capital flows and increased portfolio investment for the domestic country. This is facilitated through a legal scheme called Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). BEPS allows businesses to leverage countries with a lower tax percentage so they can shift their business operations internationally and become cost-efficient.

Due to advanced economies having more rigid regulatory policies and regimes such as interest rate limits and blockage of cross-border capital flows, corporations and wealthy individuals are incentivised to manage their affairs using OFCs in regions that offer lower tax penalties.

But privacy protection is a double-edged sword. OFCs can be used to facilitate illicit activities such as money laundering and tax evasion. To combat this, enter the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The OECD is an exclusive international organisation that focuses on policy adjustment and government collaboration. They have a set of international standards on transparency and tax that should be adhered to by OFCs. Failure to comply results in a OECD rating such as partially compliant, non-compliant or non applicable, leading to a critical loss of business and economic growth potential. Because these labels can significantly damage an OFCs business, complicity is inevitable. This complicity can be perceived as a loss of monetary sovereignty as it prevents a nation’s ability to tailor their monetary and fiscal policies to suit its own economic circumstances and priorities.

The issue arises when the OECD shapes their standards to benefit advanced economies over developing ones who rely on OFCs to expand their economy.

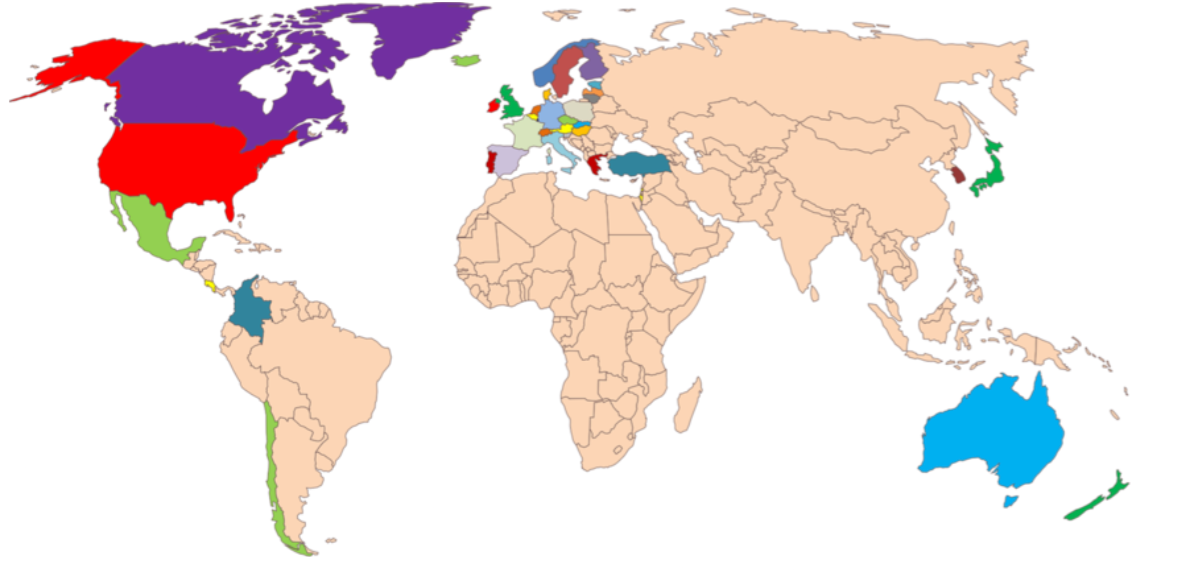

To begin, membership in the OECD is exclusive. Countries invited by the OECD council have to be unanimously approved with a strong belief that they will uphold the OECD’s values and standards. This creates an internal bias that concentrates all decision-making power amongst countries who share similar values, directly eradicating any opposing voice. Many advanced economies are not only members of the OECD but also have high tax rates. This includes the US, UK, Canada, Australia, Belgium, Germany, France, Denmark, Finland, the list goes on.

International competition has always been a crucial strategy in boosting economies because it incentivises the domestic labour force to become more productive and innovative. But, when it comes to tax competition, no longer having the upper hand, advanced economies are using the OECD to create global tax laws that limit extraction of capital flows for low-taxing OFCs. The sheer definition of political sovereignty is the ability to control your own territories and laws. It is the backbone of international law. Yet, by using the OECD as an intermediary, advanced economies are successfully manipulating changes in jurisdiction to diminish tax competition and generate higher fiscal revenue, despite most BEPS schemes being entirely legal.

Additionally, while the OECD gains support in setting their strict OFC privacy and tax standards, advanced economies remain hypocritical with their agenda. Angelo Vernados gave a critical example of this behaviour: After the horrific terrorist attack collapsing the twin towers on 9/11, 2001, the US started the war on terror. Under the impression that most funds provided to terrorist groups were shared through offshore accounts in developing countries, the US supported the OECD’s restrictive sanctions and global tax policy curated to target these OFCs that were supposedly funnelling money to terrorist organisations. In reality, most terrorist bank accounts originated in OECD member states including the US and the UK. While 20 million USD was discovered in the Bahamas, a well-established non-OECD member OFC, the branch that held the money was in fact headquartered in an OECD member state.

However, it is crucial to consider how the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) an independent intergovernmental body (administratively hosted by the OECD) can be successful in preventing OFCs from being used as accessories to shelter criminal activity. They have implemented anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terorist financing (CFT) measures. Presented as recommendations, FATF provides detailed notes and consistent updates to help OFCs mitigate emerging threats such as illicit activity characterised through digital assets. Although, FATF also rates how well OFCs comply with international standards, the difference is, their mission aligns with the objectives of all OFCs. The FATF demonstrates how bias in harmonised international standards can be eliminated when there is collective agreement.

The aforementioned arguments exemplify how advanced economies have been using the OECD as a puppet to protect their own national interests. All this, while inhibiting the growth of OFCs in developing nations, who are legally using their tax arbitrage opportunities to increase investment domestically. While organisations like FATF are helping to prevent OFCs from being used as a means to facilitate illicit activities, why is the OECD steadfast on preventing OFCs from defining their own tax and confidentiality limits? Where is the line of fairness drawn, especially when the OECD priortises the interests of their own member states?

Heer Jhaveri

Heer Jhaveri